The Maker vs Manager Problem

It’s well known that programmers dislike meetings… a lot. But have you ever wondered why programmers dislike meetings so much compared to other people? The answer is simple but obvious once pointed out: meetings are more costly to them.

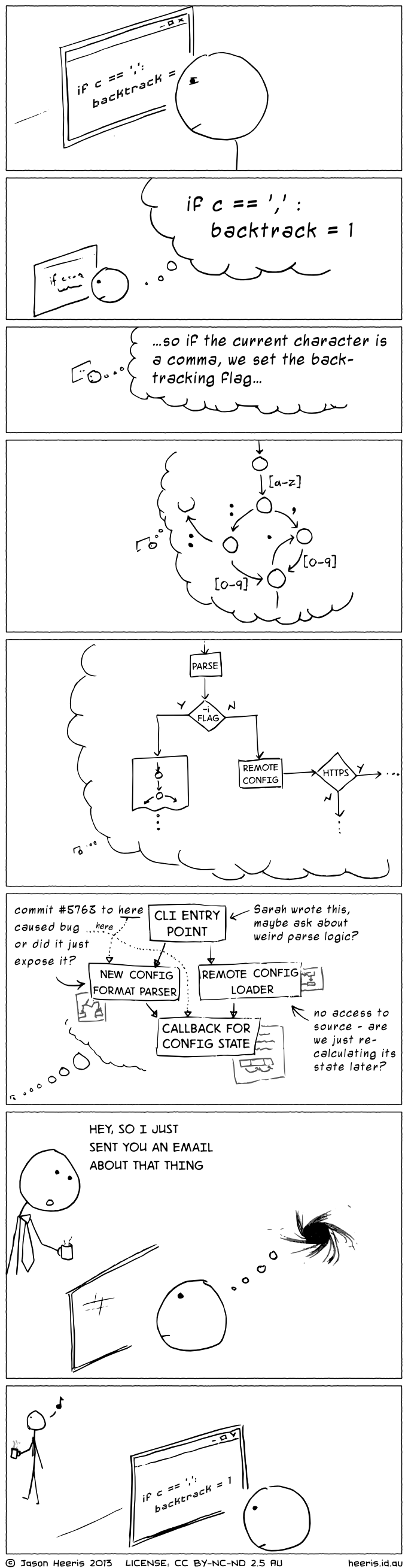

I’m sure many programmers can relate to this comic.

This blog is about the two stick figures from the comic: the maker and the manager and the fundamental problem that occurs when their schedules meet.

Note: Much of the content of this blog post is borrowed from this essay by Paul Graham. It was written in July 2009, more than 10 years ago! If you can find the time I highly recommend the original essay, it’s a classic.

Takeaway

For managers:

- Understand that the cost of an interruption is significantly higher for makers than for managers.

- The next time you want to interrupt a programmer deep in thought, think of the comic.

For makers:

- Understand that managers operate on a different day-to-day schedule than you do and respect that.

- Clearly communicate that you need long stretches of uninterrupted time to deliver great work, but be willing to compromise.

Maker’s schedule, manager’s schedule

In his essay, Graham argues that there are two different types of schedules, which he calls the maker’s schedule and the manager’s schedule.

The manager’s schedule can be thought of the traditional calendar. The day is neatly sliced into hours. You can schedule more than 1 hour for an appointment or meeting but by default you can switch tasks every hour or 30 minutes.

The maker’s schedule is different. The maker’s schedule is for programmers and writers who prefer longer stretches of uninterrupted time. For a writer or programmer it takes time to get started, it is difficult to produce something truly valuable in half an hour.

For people on the maker’s schedule, ill-planned meetings come with a cost that is both high and not immediately obvious. A single meeting can ruin a whole morning by breaking up a long period into just short enough periods where exactly nothing of value can be produced. Meetings are like the interruptions from the comic, but on a macro level.

Consider a single meeting from 10:00-11:00.

The programmer dutifully arrives at the office at 9:00. After the daily stand-up it’s 9:15 and now he has exactly 45 minutes to get some programming done. But he knows that he has a meeting at 10 so he will probably not be able to program until 10:00 exactly because of the meeting. It’s 9:30 already, shit. I’d better prepare for the meeting. Of course, the meeting is scheduled to 11:00 but runs slightly longer and after the meeting you grab a coffee with your coworkers. Now it’s 11:15 and you have 45 minutes to lunch. The programmer now has to decide whether he is going to spend 20 minutes getting into the flow to spend a mere 25 minutes programming until lunchtime.

Narrator: He didn’t.

The problem is that most powerful people are on the manager’s schedule. That’s the reason it’s called the manager’s schedule. Your manager (your boss) is most likely, without realizing it, on the manager’s schedule. This is also why its more likely that the maker will conform to the manager’s schedule, he is your boss after all.

This is the crux of the whole problem. Two different types of people with two different types of schedules. The problem is clear, but what about solutions?

Graham offers three solutions. The first one is using office hours to simulate a manager’s schedule inside a maker’s schedule.

How do we manage to advise so many startups on the maker’s schedule? By using the classic device for simulating the manager’s schedule within the maker’s: office hours. Several times a week I set aside a chunk of time to meet founders we’ve funded. These chunks of time are at the end of my working day, and I wrote a signup program that ensures all the appointments within a given set of office hours are clustered at the end. Because they come at the end of my day these meetings are never an interruption.

The second solution comes from Graham’s personal experience, but I doubt that this is sustainable in any other environment than a start-up.

When we were working on our own startup, back in the 90s, I evolved another trick for partitioning the day. I used to program from dinner till about 3 am every day, because at night no one could interrupt me. Then I’d sleep till about 11 am, and come in and work until dinner on what I called “business stuff.” I never thought of it in these terms, but in effect I had two workdays each day, one on the manager’s schedule and one on the maker’s.

For the third solution we continue to the closing remarks.

Closing remarks

It feels incredibly lazy to simply copy Graham’s words again, but they still ring true today, ten years later.

Till recently we weren’t clear in our own minds about the source of the problem. We just took it for granted that we had to either blow our schedules or offend people. But now that I’ve realized what’s going on, perhaps there’s a third option: to write something explaining the two types of schedule. Maybe eventually, if the conflict between the manager’s schedule and the maker’s schedule starts to be more widely understood, it will become less of a problem.

This is the third solution: hope and optimism. To write something clearly explaining the problem and then hoping it goes away on its own. Wishful thinking, but good wishful thinking nonetheless. In writing this essay I’ve been perhaps just as naive as Graham himself by believing in the idea that if we can show people the problem that it vanishes into thin air - exactly like the programmer’s deep thoughts when interrupted.

It is said that time reveals the truth and maybe, just maybe, we can do more about it in the coming ten years.

Comments