My experience with Domain-Driven Design part 1: naming

So I have been working a lot with Domain Driven Design (DDD) lately.

This is mainly because I have a colleague who is in love with it and it rubs off on me – and I love it.

If you are interested in this kind of stuff, these three books are essential:

- Domain driven design

- Architecture patterns in Python

- Clean architecture in Python

In this blog post I want to share my experience working with domain driven design for the first time.

Context

To give a little bit of context. I’m a machine learning engineer at Snappet. Snappet is an edtech platform that has an app where primary school children learn math and language on tablets. We build AI models to try and help them kids learn more.

We have several models running in production and we are now building a unified machine learning infrastructure that houses and supports our current models and is also future-proof enough for the new models that we are building.

What is domain-driven design anyway?

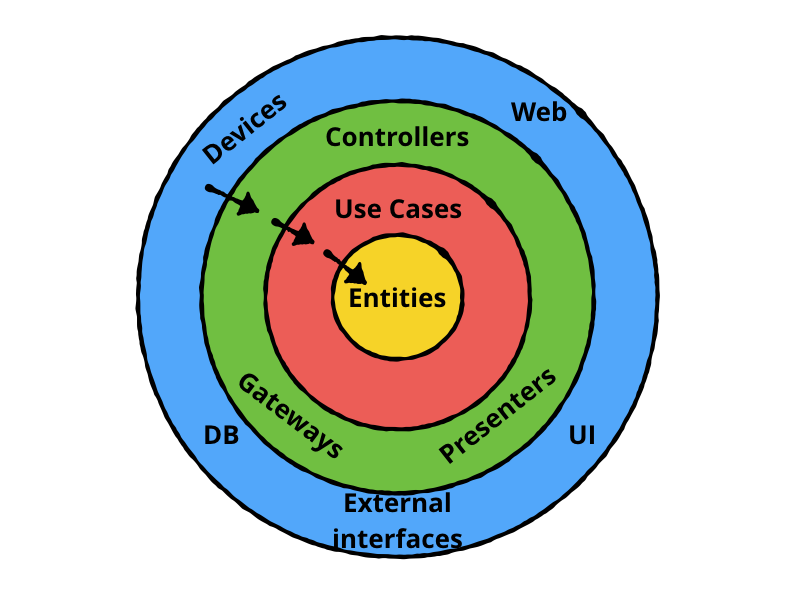

Most of what I’m writing down here is my crappy and watered-down rendition of the hexagonal/clean/onion architecture.

The key idea is that you want to design your program in such a way that you have a clear boundary between the “dirty” outside world and a “clean” inner world.

All software exists to solve some kind of business problem, and that logic of solving that problem is what we call the core business logic. We can imagine or pretend that this lives on some higher level of abstraction and that this problem can be solved by higher level abstract concepts. We can fit together these pieces of the puzzle to solve the problem that we are trying to solve. These little puzzle pieces are your domain models.

For example, if you build a code formatter then you parse the text into an abstract syntax tree (AST). The nodes and leaves of the AST are then part of your domain model. So you have the “dirty” outside world text and the “clean” concepts like nodes and leaves.

I’m probably doing a terrible job explaining domain-driven design, but this is what it boils down to in my head.

Observation 1: We made some good architectural decisions early on

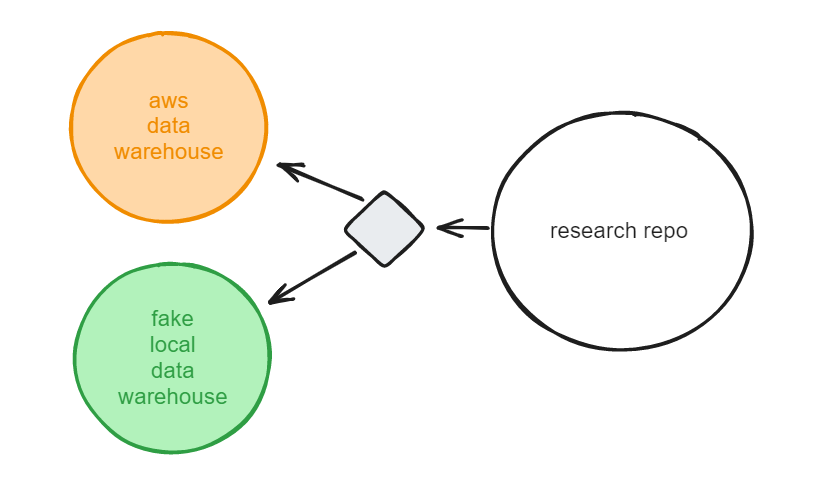

An important decision we made early on was that we wanted our tests to be completely decoupled from our data warehouse. This was driven by a desire of our developer experience to be great which meant that our tests have to run really fast and that they had to be isolated from any external systems.

We ended up with a setup similar to the picture. Our repo hits an interface which, depending on the mode of running (local or prod) we hit the fake aws setup or the real aws setup.

This was something we had never done before. It took a lot of effort setting up. However, we are happy that we spent the time and took the effort because now our tests are fast and developing really is a joy. This was definitely worth the extra effort.

Observation 2: We try to give everything a name

Another thing that I noticed was that we try to give everything a name.

Instead of nameless rows of a dataframe, we now have the domain model Data which is a dict of Fields (another domain model representing a data field for us)

# src/models/domain/data.py

Data = NewType("Data", Dict[Field, np.ndarray])

Instead of nameless arrays that come out of our models we have Predictions (or TorchPredictions, NumpyPredictions)

NumpyPredictions = NewType("NumpyPredictions", Dict[Field, np.ndarray])

TorchPredictions = NewType("TorchPredictions", Dict[Field, torch.Tensor])

Predictions = NewType("Predictions", Union[NumpyPredictions, TorchPredictions])

Instead of upload/download functions that take a string as an argument, we have an S3Path

@dataclass

class S3Path:

"""Abstraction over a normal string to cover some parsing/validating of s3 paths"""

path: str

The basic rule of thumb that I have observed here is that, if it represents some kind of concept, then give it the name of that concept.

In the beginning this feels kind of odd, but you get used to it quickly and then you start noticing some very powerful typing benefits.

Observation 3: We try to separate data and functionality

In the same vein another important observation is that we try to separate our data and functionality.

But remember the last point? Now we give everything a name!

When we get data back from a tablet it’s not just a row in a dataframe, but we give it the name Answer

@dataclass(eq=True, frozen=True)

class Answer:

correct: bool

exercise_id: int

answer_type: AnswerType

Now our models don’t take in nameless rows numpy arrays, but it takes a list of a list of Answers and it outputs a list of PupilStates

class Model:

def update(self, answers: List[List[Answer]]) -> List[PupilState]:

...

Observation 3: Tests become very lightweight

Another thing that I noticed is that tests become very lightweight because they are defined in terms of domain models.

We translate our business problems to domain models and then once we have this skeleton we only have to think about their interactions. This is nice because then we can forget about the rest.

This means that your tests become kind of esoteric, almost like they are written in a different language, but they are very lightweight because you created them (with your own domain models).

This is an example of our forward pass defined in our own domain model language:

def test_single_forward_pass():

model = BaselineModel()

data = InputData(Data({

PUPIL_ID: np.array([1, 2]),

CORRECT: np.array([1, 0])

}))

preds = model.forward(data)

assert preds == expected_preds

Wrapping up

In the beginning it felt very weird trying to cast every little thing to a domain model, but I’ve grown very fond of it.

Framing your problem in terms of domain models is nice because it really gives a language to the problem that you are trying to solve. You’re actively translating the “dirty” outside world to your “clean” pristine inner world that exists only of domain models.

Slap some interfaces on top of this and you have clean code that works that is written in such a way that it is almost impossible to write bad code.

Remember Domain-driven design is naming things for what they are

Comments