Make your Anki flashcards atomic

In Augmenting Long-Term Memory, quantum physicist Michael Nielsen explains how he uses Anki to augment his long-term memory. Nielsen explains why you should make your Anki flash cards as atomic as possible. And guess what, I didn’t. This blog post shows you the problem of a non-atomic card and how to fix it. But first, what is Anki?

What is Anki?

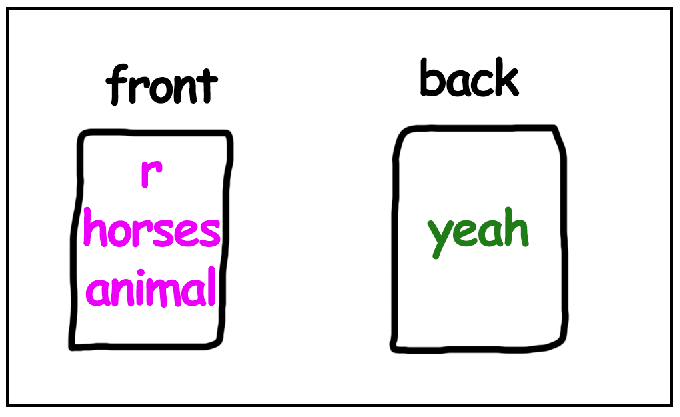

Anki is a flashcard program. It allows you to easily make flashcards and review them digitally. Anki uses a lot of smart science to figure out which card to show you and when. Consider the example card down below. It has a question on the front and an answer on the back.

Why does this matter?

This matters because fluency matters in thinking. Consider the example from my previous blog post about a hammer driving in a nail.

Imagine a carpenter that continuously has to look up how to drive in a nail! This carpenter would get nothing done! Similarly, I think we do ourselves a disservice if we do not commit programming syntax to memory.

I believe this advice is controversial. Programmers are known for having a large (albeit silent) ego as the work they do is highly intellectual. And I can definitely imagine a programmer thinking that they are “above” learning “simple and stupid” things like committing syntax to memory.

Whether you believe me or not, I am convinced committing syntax to memory will make me a better programmer. And well, if it doesn’t, at least it makes me a more fluent programmer!

The problem

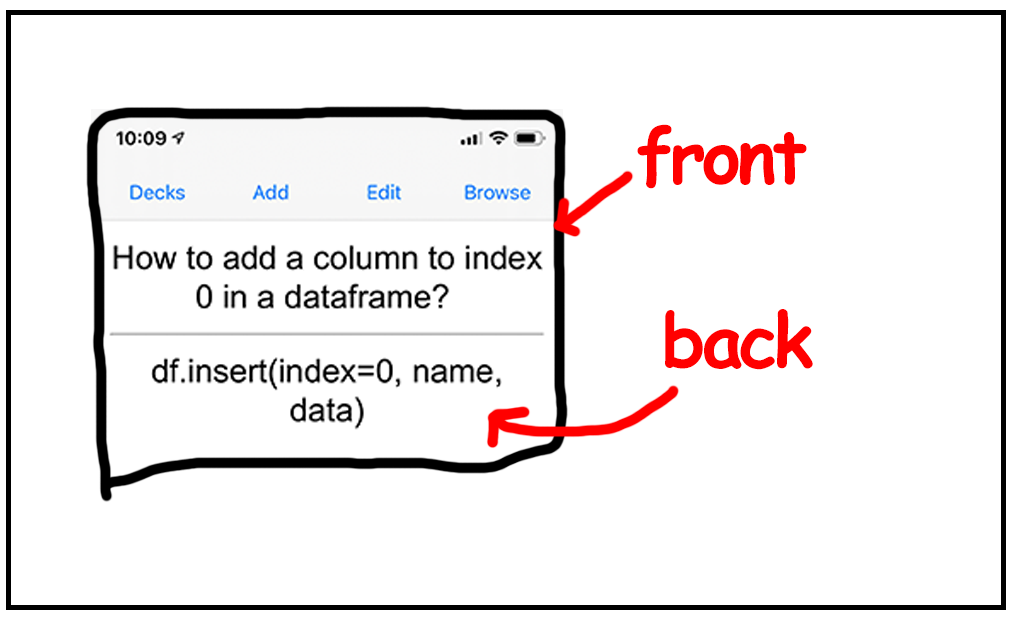

This question is the problem. I kept getting this question wrong over and over again.

In the essay, Nielsen describes several patterns of use he discovered while using Anki. Basically these are hard-fought lessons he learned while using Anki to make over ten thousand flashcards. Being the silly goose that I am, I completely ignored his advice and just made Anki cards at will.

One of the patterns described is the atomic card principle, which states that you should make your questions and answers as atomic as possible. Both the question and answer should express one and just one idea.

The root cause of my inability to commit this card to memory was because it was not atomic. It wasn’t singular. It tried to do too much.

The solution

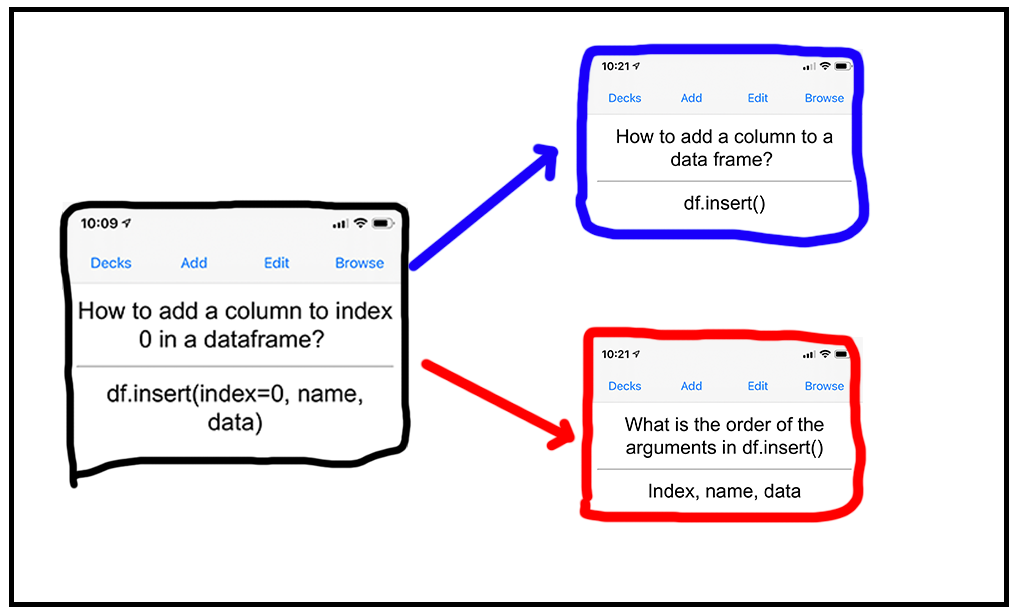

The solution to this of course, is simple. Simply split up the card into two atomic cards.

I split the more difficult card up into two simpler cards. The first one reads: “How to add a column to a dataframe?” Answer: “df.insert()”. And the second one reads “What is the order of the arguments in df.insert()” Answer: “index, name, data”.

Ever since splitting it up, I’ve had no issue remembering the two smaller cards. Funnily enough, just for the sake of it, I kept the larger card in. Now because I have cemented the knowledge of the smaller cards I can now puzzle together the larger non-atomic card as well!

Conclusion

That’s it!

I’ve showed you the atomic card principle for making flashcards and how an application of that got me unstuck. I had a bad flashcard and turned it into a good one by splitting it up.

I hope you enjoyed reading this! Agree? Disagree? Don’t care? Let me know in the comments and we can discuss! Thank you for reading!

Comments