How to build great systems

In this post I want to collect and synthesize everything I know about building systems.

💡 This post is in a draft stage. I am in the information collection stage.

Outline

- Introduction

- What is a system

- Why is building great systems crucial

- What will you get out of this post

- Understanding systems

- What is a system

- Why systems matter

- Benefits/characteristics of well-designed systems

- Simplicity, reliability, scalability, resillience, maintainability

- Principles for building great systems

- Understanding the purpose

- Aligning goals

- Incorporate Feedback Loops

- Key steps to building great systems

- Map out the process

- Observe and get the heartbeat of the current system

- Gather input from stakeholders

- Prototype and iterate

- Case Studies or Examples

- Generic system tips

- Know as little as possible

- Depending on things make

Most of my advice on how to build good systems is built on the following books:

- The Philosophy of Software Design by John Oosterhout

- Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows

Introduction

What is a system

To better understand what a system is we must first define it.

I like this definition of a system given in the book Thinking in Systems:

A system isn’t just any old collection of things. A system is an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organized in a way that achieves something. If you look at that definition closely for a minute, you can see that a system must consist of three kinds of things: elements, interconnections, and a function or purpose.

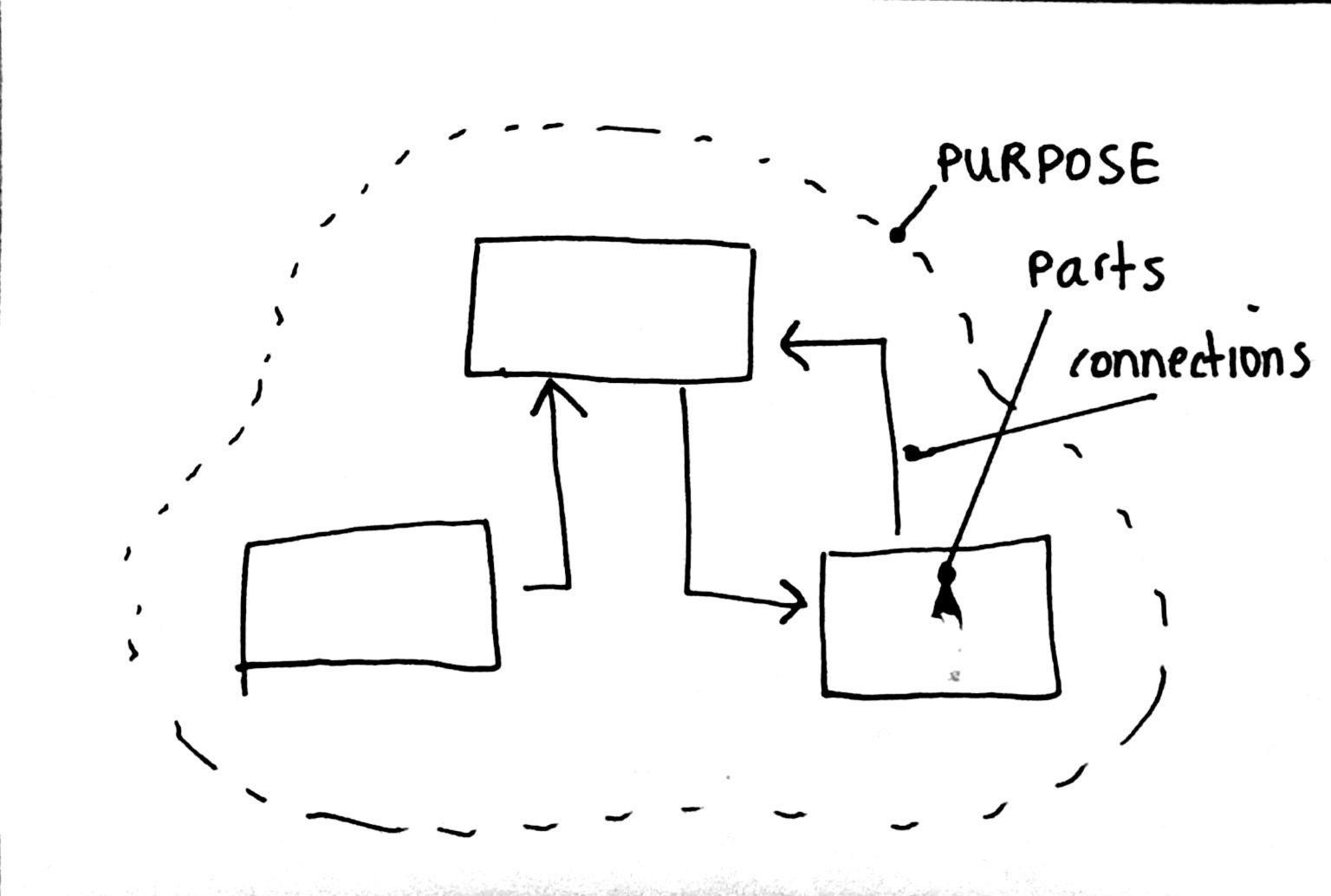

What is a system? A system consists of three parts: Its components, its connections or links, and its purpose.

When you frame it like this, almost everything in the world is a system. For example the stock market is a system. Your local football team is a system. Your team at work is a system. The way you write blog posts is a system. The way you set goals and try to achieve them is a system. Your digestive tract is a system. Everything is connected and everything is a system.

A system can not be understood by just looking at its elements

Another

One important central insight to systems theory is that a system can not be fully understood

A system can not be understood or studied by just looking at its parts. You must look further and consider its interconnections and its purpose as well.

Beyond Ghor, there was a city. All its inhabitants were blind. A king with his entourage arrived nearby; he brought his army and camped in the desert. He had a mighty elephant, which he used to increase the people’s awe.

The populace became anxious to see the elephant, and some sightless from among this blind community ran like fools to find it.

As they did not even know the form or shape of the elephant, they groped sightlessly, gathering information by touching some part of it.

Each thought that he knew something, because he could feel a part. . . .

The man whose hand had reached an ear . . . said: “It is a large, rough thing, wide and broad, like a rug.”

And the one who had felt the trunk said: “I have the real facts about it. It is like a straight and hollow pipe, awful and destructive.”

The one who had felt its feet and legs said: “It is mighty and firm, like a pillar.”

Each had felt one part out of many. Each had perceived it wrongly. . . .2

This ancient Sufi story was told to teach a simple lesson but one that we often ignore: The behavior of a system cannot be known just by knowing the elements of which the system is made.

The essence of this story is that you can not predict the behaviour by just looking at the elements of which the system is made of. However, this is the easiest thing to do because they are the most visible.

The elements are often the most visible but the least important part of system behaviour. The interconnections and the purpose of the system are less visible but maybe even more important to understand system behaviour.

Why are systems important?

Systems are important because they are everywhere.

Everything that you want to do: get stuff done, get promoted, achieve amazing things, all of these are governed by systems.

Because everything is interconnected and everything is a system we must learn how to harnass these systems and how to nudge them to the state that we want them to. We start with toy models and quickly run into the issue that the world is really messy complex and non-linear. We can never hope to control the universe, but maybe we can give it a gentle shove in the right direction.

So why do we study systems anyway? I think it’s because we want to understand, control, and manipulate these systems so that we can nudge them to whatever state we want them.

However, in reading about systems you start to realize that this is a futile effort. Non-linear dynamical systems don’t really do well with goal seeking behaviour. It’s kind of like this genie that you get three wishes from, but they are exactly what you ask for with some unintended side effects and consequences you did not expect.

What we can do however is that we can try to observe systems, we can try to understand the links and how its behaviour is latent within its structure. Maybe then we can try and work with the system and grow together and push the system in the right direction, or nudge, whatever.

What will you (the reader) get out of this post

In this blog post I will give practical experience-based tips on how to build great systems.

I will talk both about the very “systemy” part of building systems like feedback loops and dynamics but I will also talk about the very human and team-based part of building systems. Because when you really think about you are a building a machine, a factory, but who builds the machine? And who builds the machine that builds the machine, and who builds the machine who builds the machine who builds the machine, etc. It’s systems all the way down.

Key concepts

- Caching: What expensive computations can we store and then serve again without recomputing them? This works both for computations but also for static website content.

- Decoupling producers and consumers: Add a queue between a producer and consumer to decouple them. This provides a buffer and safety for if one of them inevitably falls over.

- Separate reads from writes: Often the read and write workload is vastly different. Can we exploit this and create a main write database and multiple follower read replicas?

- Horizontal scaling & load balancing: Can we scale our systems in such a way that we can simply add more machines to handle the load? This works for both servers (autoscaling) but also for databases (sharding). This does mean that we have to balance and manage this load.

I’ve written about this before here.

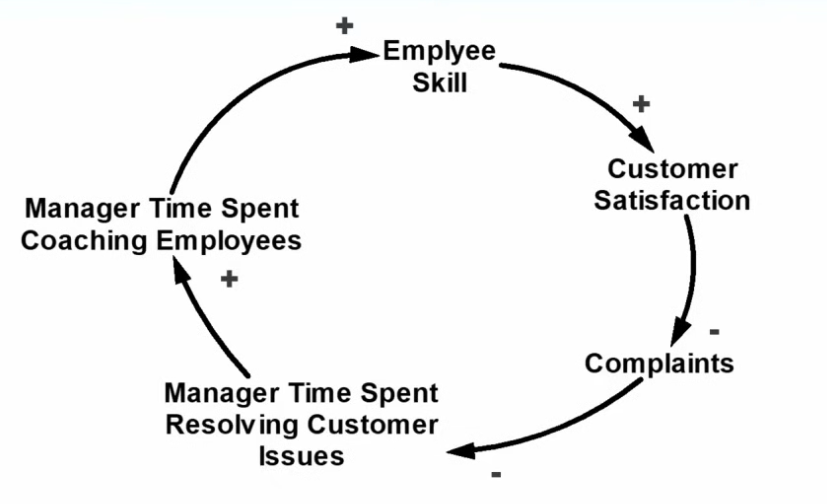

Shorten your feedback loop

If there is one thing that I want to give as advice when you are building a big system is that you want to increase your feedback loop speed. The rate at which you can try out things.

Clarify, brute-force, optimize

- Clarify: Ask clarifying questions to tease out requirements. Talk to people. Try to understand what they want to be built and why

- Brute-force: Find the simplest solution and built it

- Optimize: Find some bottlenecks in the system and optimize them

A little bit of effort goes a long way (interfaces)

Sometimes a premature optimization does make sense. I was part of a large platform migration and we took quite some time (think 2-3 weeks) to reallly think through all the use cases we wanted to build in the near future (think 2-3 years).

We analyzed our infrastructure for use cases and we sketched an API design that would both fit the old infrastructure and that would also fit our future use-cases. Usually I would categorize this as a premature optimization, but in practice it turned out that we did this really well and we built some great abstractions.

I think that this worked because we had previous experience with the model we tried to fit into the platform and because of that

Resillience

What makes systems work? The answer is resillience. The ability to spring back into operation after a system shock. The opposite of resillience is brittleness or rigidity.

Resilience arises from a rich structure of many feedback loops that can work in different ways to restore a system even after a large perturbation. A single balancing loop brings a system stock back to its desired state. Resilience is provided by several such loops, operating through different mechanisms, at different time scales, and with redundancy—one kicking in if another one fails.

The idea for resillience is to have multiple balancing feedback loops that kick in if another one fails. That does make sense.

Hierarchy and subsystems

A story about Hora and Tempus

There once were two watchmakers, named Hora and Tempus. Both of them made fine watches, and they both had many customers. People dropped into their stores, and their phones rang constantly with new orders. Over the years, however, Hora prospered, while Tempus became poorer and poorer. That’s because Hora discovered the principle of hierarchy. . . .

The watches made by both Hora and Tempus consisted of about one thousand parts each. Tempus put his together in such a way that if he had one partly assembled and had to put it down—to answer the phone, say—it fell to pieces. When he came back to it, Tempus would have to start all over again. The more his customers phoned him, the harder it became for him to find enough uninterrupted time to finish a watch.

Hora’s watches were no less complex than those of Tempus, but he put together stable subassemblies of about ten elements each. Then he put ten of these subassemblies together into a larger assembly; and ten of those assemblies constituted the whole watch. Whenever Hora had to put down a partly completed watch to answer the phone, he lost only a small part of his work. So he made his watches much faster and more efficiently than did Tempus.

Complex systems can evolve from simple systems only if there are stable intermediate forms. The resulting complex forms will naturally be hier- archic. That may explain why hierarchies are so common in the systems nature presents to us. Among all possible complex forms, hierarchies are the only ones that have had the time to evolve.5

Step 1: Gather requirements

The first thing you want to is you want to gather requirements. This makes a lot of sense and it almost sounds like trivial advice. But sometimes it is worth repeating trivial advice in case you make mistakes.

The reason I am singling out step 1 is because it is very tempting to just start building. But what really the first step is that you should do is that you should talk to as many people as possible and try to tease out what everyone wants.

Asking once is not enough, you really want to drill down on a list of things that needs to be built and then prioritized. The reason for this is that it is actually when you think about really unclear what to build and this will remain so until you uncover what really is the ask behind the ask.

You should gather the requirements and write them down so that everyone agrees on them but you should also try to understand where these requirements are coming from. The reason for this is that the requirements that people say they want and that you write down are just a single reflection of what they truly want but are unable to express whatever it is that is inside their heads.

Stakeholder management doesn’t really exist

If you need to manage your stakeholders, you messed up somewhere along the way.

In general, I don’t really believe in stakeholder management. If you need to manage your stakeholders you did something wrong. Most likely you undercommunicated about what exactly you were going to deliver, but sometimes you might be trying to deliver the wrong thing.

Stakeholders will notice that you are delivering the wrong thing, be critical, and that’s how you manage your stakeholders. But what I’ve learned is that everything that stakeholder management is that you should learn and pull whatever wishes your stakeholders have and then deliver exactly that what they want for.

Dependencies

When you draw a box with an arrow you draw a dependency. System dependencies are a lot like software dependencies. Here you can draw anything you want but only the most important things should be noted. Note that there are explicit dependencies and implicit dependencies. Just like in software.

Fundamental shifts take time

At some point I was part of this team working on machine learning infrastructure. But it turned out that the first team that built the infrastructure had made a huge mistake in picking the domain. What they did was that they married themselves to an implementation detail of a certain machine learning model. This model formed the basis of all other models further down the line. This worked very well in practice, but it made it hard to productise new types of models.

The moral of the story is this. Switching and decoupling from the original model which we married to the implementation detail with to switching to a new type of more generic model took time and is still not finished. These things take a long time, think in the span of 3 years, because all the legacy systems are built on the older version, and it will never get prioritized until there is a good reason to do so, because the old system “just works”. It takes a single person with a single minded vision to pull this off and an incredible amount of patience. It really takes multiple iterations over multiple years where many things can go wrong, timing, people leaving etc.

Conway’s law

In simple words Conway’s law states that you “ship your org chart”. Whatever the system state your organization looks like, that is what you will ship. This is something that you can read about but to really experience it and to experience it first-hand through team shifts is something else.

The reason why this is the case is because I think that work happens in teams. And teams are structured around a certain way of communicating that is unique to their team, but also siloed to their team. Each team has their own board and that is the vessel or the structure in which work happens. A natural byproduct of this is that you ship your org chart because you ship whatever you are working on in your team.

In that sense, your team effectively becomes an abstraction, a module, hidden behind the product owner as an interface. These are then loosely coupled and highly cohesive. But is this really the best split for everyone?

Having been part of many different teams over the years, you will start to feel this “law” in your bones and start to appreciate its power. The corrollary of this is that if you want an organization to ship something you should structure the information flows and the team flows in such a way that it will ship whatever you want it to ship.

See also:

- https://martinfowler.com/bliki/ConwaysLaw.html

Systems are boxes and arrows

Simply put systems are just boxes and arrows.

The boxes are the elements.

The arrows are the connections between the two.

The purpose is what you don’t see, but that’s the invisible driving force connecting all the parts.

Always optimize system output

You always want to be optimizing system output. Whatever that means.

It can be team output. It can be org output. It can be your household output.

However, avoid optimizing for your own gain at the expense of the system output.

A system consists of three things: its parts, its connections, and its purpose

A system consists of three parts

So, what is a system? A system is a set of things-people, cells, molecules, or whatever-interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time. The system may be buffeted, constricted, triggered, or driven by outside forces. But the system’s response to these forces is characteristic of itself, and that response is seldom simple in the real world.

https://medium.com/@andrewsavikas/thinking-in-systems-db72c0f00adf

This is a nice quote

Putting different hands on the faucets may change the rate at which the faucets turn, but if they’re the same old faucets, plumbed into the same old system, turned according to the same old information and goals and rules, the system behavior isn’t going to change much.

Loops

Reinforcing loop

Reinforcing loop is a loop where the loop “runs away” can also be in the negative side. It can be a virtuous or a negative reinforcing loop. Like past standards setting current standards.

Balancing loop

Balancing loop is also called goal seeking loop

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o-Yp8A7BPE8

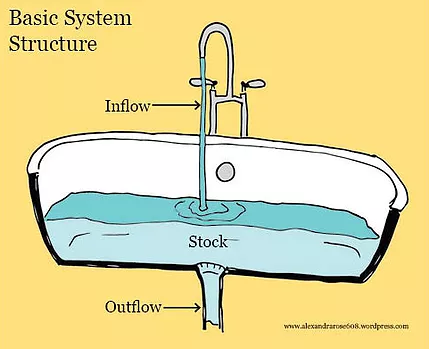

How to you fill a tub

System bottlenecks

I’ve written about this here, and it is repeated in the Meadows book:

At any given time, the input that is most important to a system is the one that is most limiting.

In other words, in every system you always want to be optimizing the system bottleneck. Otherwise you are not adding any value. I do see one alternative where you can optimize a non-bottleneck to create a build up or a buffer of value which you then want to release all at once by then flashing the bottleneck open, but this is an edge case I think.

Modules should be deep

Google is deep.

ChatGPT is deep.

They have a deceptively simple interface for the complexity that is hidden beneath them. They are almost like an iceberg, whatever you see and interact with is simple and small, but the hidden complexity beneath it is enormous.

Amazon is deep.

Amazon’s interface is as simple as it can get. Within a couple of clicks you can get something shipped to your doorstep. That is nothing short of magic when you ask me. I’m not talking about the environmental impact of this, but it’s the closest thing we have to wishing something and it’s just materializing on your doorstep the next day.

A car is deep.

A car’s interface with a steering wheel and some pedals (forgetting about the clutch for now) is also a deceptively simple interface that is very powerful. You don’t need to know how a car works to use it. It might help in debugging options, yes, but you don’t need to know the internals to wield it, and that is powerful. You don’t need to know how ChatGPT works internally to use it. You don’t need to know how a hammer works to smack something with it.

Tip: Minimize total system complexity

Often times I am talking about system development in a professional setting. That means we a building systems for a certain company in our professional capacity.

What we want to do is always minimize total system complexity. Imagine that there is a solution that takes on a bit more work for ourselves and our team, but improves the total system complexity (so that we make our organization’s life easier) then we should do that and take that action.

Quote

If a factory is torn down but the rationality which produced it is left standing, then that rationality will simply produce another factory. If a revolution destroys a government, but the systematic patterns of thought that produced that government are left intact, then those patterns will repeat themselves. . . . There’s so much talk about the system. And so little understanding. —Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

This ties in with the thought that it the system that gets produced, but it is the minds and the ideas that actually create the systems, the ideas and minds that trascend the paradigm in which the system exists, only that has the power to create and destroy the systems of which they are themselves a part of.

Slinky

The book opens with this quote

Early on in teaching about systems, I often bring out a Slinky. In case you grew up without one, a Slinky is a toy—a long, loose spring that can be made to bounce up and down, or pour back and forth from hand to hand, or walk itself downstairs.

I perch the Slinky on one upturned palm. With the fingers of the other hand, I grasp it from the top, partway down its coils. Then I pull the bottom hand away. The lower end of the Slinky drops, bounces back up again, yo-yos up and down, suspended from my fingers above. “What made the Slinky bounce up and down like that?” I ask students. “Your hand. You took away your hand,” they say.

So I pick up the box the Slinky came in and hold it the same way, poised on a flattened palm, held from above by the fingers of the other hand. With as much dramatic flourish as I can muster, I pull the lower hand away. Nothing happens. The box just hangs there, of course.

“Now once again. What made the Slinky bounce up and down?” The answer clearly lies within the Slinky itself. The hands that manipu- late it suppress or release some behavior that is latent within the structure of the spring.

That is a central insight of systems theory.

It is not the hand that causes the slinky to move back and forth. The motion of the hand suppresses and releases behaviour that is latent within the structure of the spring, which in this case is an analogy for the system.

Stocks

This is largely from the summary at the end of Thinking in Systems.

A stock is a memory of the history of changing flows within the system.

If the sum of inflows exceeds the sum of outflows. The stock level will rise.

If the sum of outflows exceeds the sum of inflows, the stock level will fall.

If the sum of inflows equals the sum of outflows, the stock level will not change.

These sound like lame truths, but they need to be said out loud.

A stock can be increased by decreasing its outflow rate as well as by increasing its inflow rate.

Stocks act as delays or buffers or shock absorbers in systems.

Stocks allow inflows and outflows to be decoupled and independent.

Tip: Complexity is caused by obscurity and dependencies

Complexity in big systems is caused by two things: obscurity and dependencies. Obscurity can be improved by making things clearer. This means making things more obvious. Dependencies however, need to be managed. Dependencies need to be made explicit where possible.

I had a situation at work where we were accidentally relying on another subsystem finishing before our subsystem because we were dependent on some files created by the other subsystem. But this dependency we did not have clear in our heads and this led to a very interesting bug that we had to figure out.

Tip: Know as little as possible

I was in this situation at work where we had a subsystem that took in JSON events and stored them somewhere. It then turned out that we did not need to know about this JSON structure at all and a binary blob would also suffice. We turned this into a binary blob and because of that we could make some significant storage optimizations because we did not have to parse JSONs anymore, we just had to store some binary blobs.

Some practical system advice

First. Get the beat of the system.

The first thing to do is not to intervene in a system but to get the beat of the system.

Look around and talk with people. Try to understand why the system does what it does.

Can you find some actual data on this and make some graphs?

First pay some attention to what the system is and why it is doing what it’s doing.

Second. Get your mental models exposed to the light of day.

This is true system’s advice. Make some boxes and diagrams and draw some arrows.

Everything we build is a model anyway, but writing them out in the form of boxes and arrows forces you to think about your assumptions and clarify them on paper.

This is similar like writing to learn.

Third. Honor and distribute information.

Decision makers can not respond to informaton they don’t have. Information is the glue that holds systems together and that makes feedback loops work or not.

Most of what goes wrong in systems is because of biased, late, or missing information.

Fourth. Use language precisely

In fact, we don’t talk about what we see; we see only what we can talk about. Our perspectives on the world depend on the interaction of our nervous system and our language—both act as filters through which we perceive our world

Our language is a filter through which we see the world.

A society that talks about being “productive” but doesn’t understand it makes “resillient” become productive instead.

Fifth. Pay attention to things you can not measure

If measureability is the thing that becomes important then you start to focus on things that become measureable. But what are things like quality and beauty, can you measure those?