How to write good code

In this mega blog post I try to write down everything I know about how to write good code.

Someone recently asked me “Can you help me improve my code?” That got me thinking, and writing, and thinking and writing, and before I knew it this blog post spiraled out of control.

💡 This post is in a draft stage. I am in the information collection stage.

This is the blog post I want to be able to link people if they ask me this question again.

Good code is very contextual, that means that this blog is highly opinionated and biased towards professional development. What constitutes as “good” in this context is very different from say a student writing his master’s thesis.

Writing good code is simple, but not easy and can be summarized in a single sentence:

💡 How do we write good code? Write code that is easy to change

Great software consists of three things: A solved problem (think: hexagonal architecture and domain-driven design), a solid testing strategy that proves that you’ve solved the problem, and some thoughtful thinking about the interfaces and interactions between components.

I’ve read countless books on how to write good code and this is the advice comes back over and over again in different forms.

- Writing tests makes your code easier to change because it can catch regressions

- Using domain-driven design makes your code easier to change because the problem is solved in the domain space

- Input output validation makes your code easier to change because you’re not afraid of regressions

- Interfaces make your code easier to change because a change in the interface is exactly propagated to all the other places that need change (the implementations)

- Good design makes your code easier to change because things that don’t change often (the interfaces between components) are well-designed

- Fast tests are nice because they provide a tight feedback loop for you to change code

- Good variable naming makes your code easier to change because it helps to build up a mental model of the code

- Etc.

What I’ve written before about

Next to all the other advice that exists already on the internet, what have I written before about?

Broadly speaking I talk about three categories on my blog: domain-driven design, interfaces, and testing strategies.

For intermediate to advanced programmers I think that writing good code comes down to having a solid solution of the problem in an abstract world that I call the “domain” space or the problem space. And then you want to express this solution in code using strongly typed (or type-hinted) objects. A programming language like Rust with its type checker is ideal for this, but you can get pretty far using type hints in Python.

Once you have this design nailed down, it becomes harder and harder to write spaghetti code because all the wirings between components are well-defined and designed (by virtue of good design).

You have lightweight domain objects that you can individually create, and test, and there are no big bulky real world objects that you are slinging around. You are truly solving the problem in the abstract domain space.

Domain-driven design/theory building/solving the problem in the domain space

- In this blog post I talk about how to solve problems “in the domain space”

- In this series of 3 blog posts I talk about domain-driven design and specifically how to use better naming to name things

- In this blog post I talk about how documentation should be like vacation photos, which talk about theory building

- In this I talk about a paper of Naur (1985) which talks about theory building. Similar to solving a problem in an abstract domain space

Interfaces/Dependency inversion/hexagonal architecture:

- In this blog post I write about the hexagonal architecture

- In this I talk about how you should validate your inputs and outputs using Pydantic. Now I know that this is a special case of parse don’t validate

- I write about inversion of control this post

- I write about how the argparse is not your interface of the application, with which I mean that it is merely an adapter in this blog post

- In this I write about how to use interfaces when implementing third party libraries

- In this blog post I talk about collaboration using interfaces as contracts.

- In this blog post I talk about how to write better code using interfaces.

- In this blog post I talk about pushing IO to the boundaries, this is a trick learned from functional programming I think

Testing:

- In this blog post I talk about test-driven design and how it can catch regressions

- In this blog post I talk about co-locating tests and source code. Things that evolve together should stay together

- In this blog post I talk about how rust co-locates test and source code as well

- In this blog post I talk about using pytest fixtures over normal test data

What is good code?

Introduction

If we want to write good code we must first make clear for ourselves what it means to write good code.

It turns out that good code is code that:

- Solves an underlying problem

- Is easy to understand and modify

- It uses interfaces and abstractions liberally

Code is written by humans (plural) for humans (plural)

“Programs should be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute.” – Unknown

Code is collaborative.

When you start developing code professionally you start working in teams. This means that you will have to interface with other people through code. This means writing code in a way that is clear and understandable for other people other than yourself.

In other words, because code is written by humans and for humans, we must try to make it as easy as possible for other people to understand and to modify. At some point you start writing software that is the product of collaboration, and this changes what it means for code to be good. Correctness is not necessarily the only thing anymore, understandability and extensibility also become important.

This is what I’d like to call the collaboration argument.

The best code is no code

“I believe it was Bill Gates: “Measuring software productivity by lines of code is like measuring progress on an airplane by how much it weighs.”

The best code is no code.

Code is not an asset, but a liability.

If you can solve the problem in less lines of code, do it. Why? Because fewer lines of code means less things to maintain which means you can spend more time on each line.

Do not pride yourself into using lines written but instead think of it as lines spent.

The best code is a solved problem

The best code is no code (and a solved problem).

Writing code should not be the goal in and of itself.

The code exists to solve a certain problem. If you can solve the problem without code, do that instead. Always try to keep this goal in mind. If you can avoid writing some code by talking with someone and solving the same problem, then do that. Do less, but better.

Code models an underlying problem

One thing that I want you to take away is that code models an underlying problem. Just like any other mathematical model models an underlying problem, we all make assumptions to solve these problems and these can be suddenly invalidated. For example, imagine Google Maps in a war-torn area. The software works but the underlying nature of the problem has shifted so dramatically that it is not up-to-date anymore. The code models an underlying problem but the problem has shifted dramatically.

Try to solve the problem in the domain-language of the problem and then translate that to code. Or have the two stay as close to each other as possible.

Good code should be easy to change

💡 How do we write good code? Write code that is Easy To Change (ETC)

A tale of two values

From: Clean Architecture

What which of these two codebases do you prefer? One that doesn’t work but you can change or the other which works but you can not change?

Function or architecture? Which of these two provides the greater value? Is it more important for the software system to work, or is it more important for the software system to be easy to change?

If you ask the business managers, they’ll often say that it’s more important for the software system to work. Developers, in turn, often go along with this attitude. But it’s the wrong attitude. I can prove that it is wrong with the simple logical tool of examining the extremes.

- If you give me a program that works perfectly but is impossible to change, then it won’t work when the requirements change, and I won’t be able to make it work. Therefore the program will become useless.

- If you give me a program that does not work but is easy to change, then I can make it work, and keep it working as requirements change. Therefore the program will remain continually useful.

The essence of good design

The essence of good code design is that it is easy to change.

The world is full of people trying to sell you specific knowledge about how to write good software. There are lists, acronyms, patterns, diagrams, docks and many other things that try to tell you how to write good software. And then here I am as well. I am trying to tell you exactly how to write software.

But there is a silver bullet. There is one.

And that one silver bullet is this: Good design is easier to change than bad design.

All patterns, all techniques, all tooling that help you write good code like the hexagonal architecture, decoupling, and the single responsibility principle. All these things are special cases of this rule that they make your code easier to change.

Why is decoupling good? Decoupling is good because when you isolate concerns you make things easier to change.

Why is the SRP good? The SRP is good because a change in requirements is then reflected in only one module.

Why is good naming important? Good naming is important because to change code you need to read it.

Why is the hexagonal architecture good? Because when you want to change the technical infrastructure, it should be decoupled from the actual problem that you’re solving. Making the code easy to change.

This is the main principle underlying all other principles: good code should be easy to change.

Complex versus sophisticated

From: A Philosophy of Software design

For the purposes of this book, I define “complexity” in a practical way. Complexity is anything related to the structure of a software system that makes it hard to understand and modify the system. Complexity can take many forms. For example, it might be hard to understand how a piece of code works; it might take a lot of effort to implement a small improvement, or it might not be clear which parts of the system must be modified to make the improvement; it might be difficult to fix one bug without introducing another. If a software system is hard to understand and modify, then it is complicated; if it is easy to understand and modify, then it is simple.

The lifetime of code

Code starts in the head of a coder. He searches and finds inspiration from his own knowledge and the code he finds in other places, and with that he writes new code. This code is added, committed and pushed into a new repository and from there on it takes a new life. It stays there, it gets maintained by his coder, and once he leaves, by other coders, maybe, at some point, it will be deleted, but this will be unlikely. It is there to stay, forever, maintained.

I am writing this as we are at the precipice of Gen-AI coding, so I don’t know how long this might be true for. But it is true now.

Code spends most of its time in maintenance mode

“Code is read more often than it is written.”

A funny thing happens when you work at any company long enough. You work on a project, write some code, you finish the project, and then a year later you actually have to revisit your old project, and you wonder who wrote that piece of crap. You realize it was you who wrote it.

This is a special case of a principle that code is read more often than it is written. Another way of framing this is that the second you write and commit the code it goes in maintenance mode. If you have a healthy project with a lifespan of 2 years, and it takes around a week to write the code, that means that it spends more than 99% of the time in maintenance mode (1 week coding versus 103 weeks maintenance). Good code should be maintainable.

This is what I’d like to call the maintenance argument.

Complexity (A Philosophy of Software Design)

Introduction

The study of software is a study in complexity. We are taking information from some place, doing something with it, and putting it somewhere else. Fundamentally this feel and sounds very simple, but we all know what a mess we can make for ourselves.

This piece talks about complexity, what is it, how can we reduce it, and why does it seem to always creep up on us without us noticing?

Essential and accidental complexity

The study of software is basically a study of complexity.

What is complexity? How can we see if a system is complex? Why is working on complex systems hard? Are there ways for us to reduce it?

There are two types of complexity: essential and accidental complexity.

- Essential complexity: Is the necessary complexity needed to perform a certain task. This complexity, at some level, is fundamental. If you want to do anything of significance you must have a certain minimum set of operations that do whatever you want to do.

- Accidental complexity: This is basically all the complexity that you add while trying to achieve the essential complexity. This is everything that is not essential. The trick is to eliminate and minimize this type of complexity.

Two ways of dealing with complexity

There are two ways you can deal with complexity, both the essential and the accidental type.

- Eliminate complexity: The first way of dealing with complexity is to eliminate it. This is obviously good if it is possible. But often it is not that straightforward.

- Encapsulate complexity: The second way of dealing with complexity is to encapsulate it. That is, can we hide the complexity of a certain module in the implementation such that when we are not working with it, we are not exposed to this piece of the complexity of the puzzle?

This is also the goal of modular design. The goal of modular design is to be able to work on a certain system without being exposed to all the complexity of the system. This is achieved with encapsulating complexity. There still is a certain amount of complexity in the system, but it is conveniently hidden for you when you are working on the system. The pieces of complexity that you are exposed to are expoed to you through the interface, its complex implementation is hidden by the interface.

What is complexity?

Can we define complexity?

The book defines complexity as “Complexity is anything related to the structure of a software system that makes it hard to understand and modify the system”

This definition of complexity mirrors the essence of good design from: “Software should be easy to change” and most of the other books I’ve found.

This means that a system can be large and sophisticated, but if it is easy to change and easy to work on then the system is not complex in our vocabulary.

Burn this definition in your head: complexity is everything that makes code harder to change.

Architecture

What is architecture (clean architecture)

So when we hear architecture, we hear sounds and visions of power and mystery. We think of weighty decisions and deep technical prowess, right? But what actually is software architecture? What does it do and when do you do it? The architecture of a software system is to shape given to that system by those who build it. The form of the shape is in how the system is divided into components, how they are arranged, and in the way that they communicate with each other. So in a sense, architecture is the invisible glue holding all the pieces together. Now we must never forget that the purpose of this shape is to facilitate the development, deployment, operation and maintenance of the software inside of it. The primary purpose of the architecture is to support the whole life cycle of the system. Good architecture makes the system easy to understand, easy to change and develop, easy to maintain and easy to deploy. The ultimate goal is to minimize the lifetime cost of the system and to maximize programmer productivity.

What is architecture (clean architecture in python)

Every production system, every package, every medical mechanical device, or every action actually is made of components and the connections between them. The purpose of these components is to use the outputs of the components as inputs into some other components in order to perform a certain set of actions. In this process, the architecture specifies which components are part of an implementation and how they are interconnected.

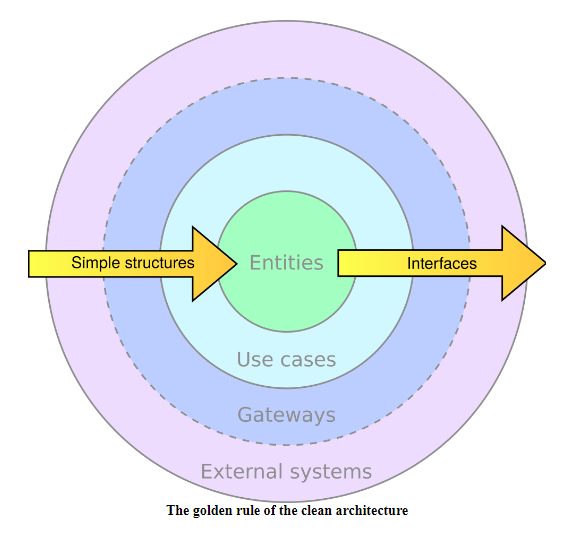

The Golden Rule (clean architectures in python)

The Golden Rule: talk inwards with simple structures, talk outwards through interfaces.

Your elements should talk inwards, that is pass data to more abstract elements, using basic structures, that is entities and everything provided by the programming language you are using.

Your elements should talk outwards using interfaces, that is using only the expected API of a component, without referring to a specific implementation. When an outer layer is created, elements living there will plug themselves into those interfaces and provide a practical implementation.

General tips and tactics

Separate data and computation

In your design you often have data (things or nouns) and you have things you do (computations or verbs). If you separate these two in your design then your whole program often become clearer and more obvious.

General Principles

- Dependency injection

- Information hiding / leaking

- Cohesion and coupling

- Separating data from computations

- Domain modeling and lightweight domain objects

- Input and output validation

- Separating tech from problem solving

- Local first

Prefer local to cloud

If you can, try to get your whole stack up locally.

You want to keep your debug loop as fast as possible. When you have your whole stack up locally that makes it easy and fast. If you have to wait for infrastructure to spin up in the cloud you are setting yourself up for failure.

Having things locally makes everything fast. Having to interface with the cloud takes time. Try to do as much as you can on your laptop. Why? Because this leads to quick feedback cycles and quick feedback cycles are important for you to figure out whether what you did was right or not.

Example: Instead of testing s3 directly, spin up a copy of moto using docker-compose instead.

Automate tedious commands

It is OK to copy-paste 5 lines sometimes. But if you do it 3 or more times try to turn it into a simple script or makefile. Get into the habit of automating the boring stuff, this will, in the long-term, free up more time than you might think.

Running make build feels great and snappy.

Let the computer do the work. Automate the boring stuff.

Keep your feedback loop short

Try to make your feedback loop as fast as possible. This means for example having lightweight objects and writing tests for those objects. This means for example disabling steps in the pipeline so that you can run the tests faster. I am debugging a Docker pipeline now and I do not want to wait for the docker build every time, but I am not changing the code, so I just disable the step, so I can get faster to where the point that I’m trying to fix things. Make your feedback loops short, so you get quick and timely feedback.

Generic test advice

Generic testing advice.

If writing tests is hard, something is wrong with your code

It is often the case that test suites are slow and that tests are hard to write. If this is the case then that probably means that there is something wrong with your design. Code should be designed in such a way that tests are easy to write (and fast).

Tests should prove the correctness of your code

Write tests to verify the correctness of your code. When someone is reviewing your PR he should not read your code to check the correctness of it. Your tests should prove the correctness of your code.

Bugs in production should always be turned into a new test

When a production outage occurs or some bug occurs in production. You want to make sure that it gets turned into a new test case that you can run. Because how are you otherwise going to make sure that this bug won’t appear again? This is what we call a regression.

Unit tests should be fast

Unit tests should be fast. Unit tests should run in the order of seconds, preferably even milliseconds. You should run your unit tests often and they should not be a pain to run. If you feel like your unit tests take too long to run then that is a symptom of a larger problem. Probably you are hitting some external system that you do not want to hit.

Put your unit tests close to your source code

Conventional wisdom says that you should have a src folder and a tests folder. I disagree. Put your source code in files like src/foo.py and put your tests in src/foo_test.py. This convention is borrowed from golang and rust. I like this convention because it promotes test code to be a first-class citizen. Testing no longer becomes an afterthought but it will garner the same attention and care as your other source (production code).

Integration tests should test the whole flow of the program

Integration tests should be a complete test of your system how the user would use it. This is basically an external API call to your system. How would someone use the interface that you expose to them? I put these in test/ because I feel like this gives the distinction that they are external. These tests are heavy and often slow, don’t have many of them.