Show your work: Implementing a data sequencing step in a machine learning pipeline

I thought it would be fun to take you along a ride of what I actually do as a machine learning engineer.

For context, I’m a machine learning engineer at Snappet which is a startup in the edtech space. Snappet is a sort of Duolingo for dutch primary schools. We have built an app that teaches kids math on tablets and I then specifically build machine learning models to try and help them learn more! Super exciting!

show your work

This is another entry in the show your work series where (duh) I show some of my work.

These are some of the older entries:

- Show your work: Writing complex SQL queries

- Show your work: Automating cloud infrastructure using infrastructure-as-code

big picture

We have several machine learning models running in production and we are building the 4th one. The problem with this is that you also end up having 4 different infrastructures running alongside each other.

Having to maintain 4 different infrastructures is a pain, and because have done this 3 times before already we feel like we are confident enough now to say which abstractions work and which ones don’t.

When you are generalizing something you don’t want to do it too early because that would be premature optimization, but you also don’t want to do it too late because then you have wasted effort. We believe that we can, after the third time, build a framework that will encompass all our other models and that is will see us through the forseeable future.

problem

So what is this piece of the pipeline about? The problem is that some of our models work with raw observations and some models work with sequenced observations. Because we are trying to build a unified model infrastructure our infrastructure should be able to handle both.

This piece of work is about implementing the data sequencing step that takes the raw data that we have as observations and sequence them into little neat arrays that our model can use.

preparation

I have found it enormously helpful to spend some time upfront investigating and preparing. Avoid wasting time by asking validating questions and coming up with a plan/design before you start coding.

I made a little plan, asked alignment and feedback from the team, and once we all agreed it was time to start coding!

implementation (start with a test)

The first thing we do when we make a new feature is to write an integration test for it:

def test_sequence_e2e_local_warehouse():

args = Namespace()

main(args)

This led me to write the new entrypoint with the right arguments:

def parse_args(args):

parser = ArgumentParser(formatter_class=ArgumentDefaultsHelpFormatter)

parser.add_argument("--s3_data_location", ...)

parser.add_argument("--sequence_length", ... )

parser.add_argument("--output_s3_location", ...)

args, _ = parser.parse_known_args(args)

return args

if __name__ == "__main__":

args = parse_args(sys.argv[1:])

param_dict = copy.copy(vars(args))

logger.info(f"Using arguments {param_dict}")

main(args)

The main functionality is handled by what we call an “Orchestrator” which is just a fancy word for “a thing that combines other things but doesn’t do anything on it’s own”.

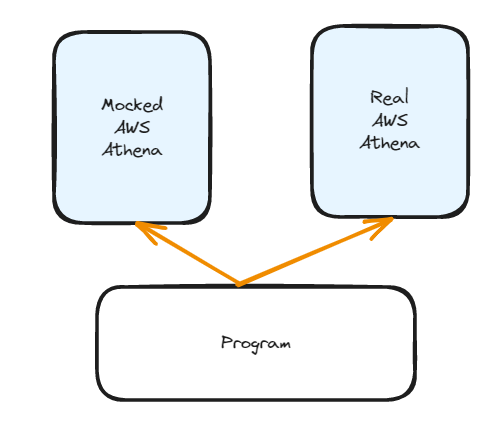

In general we don’t want to depend on calling AWS when we are testing so we have built two different warehouses, sometimes also called repositories. We have the LocalWarehouseService which duplicates the behavior of AWS locally, and we have the AthenaWarehouseService which is a connection to the real AWS Athena that we call during prod.

def main(args: Namespace):

if os.environ.get("MODE", None) == "local":

logger.info("Running in local mode")

warehouse_service = LocalWarehouseService(

s3_client=mock_s3_client,

)

else:

logger.info("Running in prod mode")

warehouse_service = AthenaWarehouseService(

athena_connection=athena_connection,

)

orchestrator = DataSequencingOrchestrator(warehouse_service=warehouse_service)

orchestrator.orchestrate(args)

Here you really see the beauty of the hexagonal architecture shine through. We can now build a single data sequencing orchestrator that has two different implementations based on where we are: testing and production.

Then I got started on implementing the orchestrator.

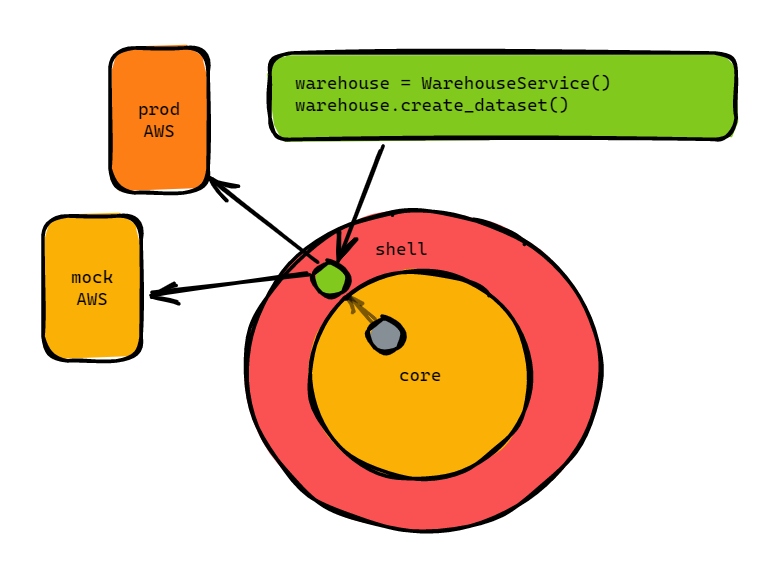

We have been using (and liking) the orchestrator pattern recently. This is a pattern that takes in some services (things that do things) and ties them together for different use cases.

In this case we have a data sequencing orchestrator that ties the different services together and calls them with the right arguments. A key characteristic of the orchestrator is that it isn’t allowed to do anything new itself. It is only allowed to call the interfaces of the services injected into it, like this:

class DataSequencingOrchestrator:

def __init__(self, warehouse_service: WarehouseServiceInterface):

self.warehouse_service = warehouse_service

def orchestrate(self, args: Namespace):

"""Ties the whole routine together and executes everything."""

self.warehouse_service.sequence_dataset(

s3_data_location=args.s3_data_location,

sequence_length=args.sequence_length,

output_s3_location=args.output_s3_location,

subset_name="train",

)

...

For now, we just show the train step. The validation step is trivial to implement later on.

Note that we have a warehouse_service that is an implementation of the WarehouseServiceInterface, that is how we keep the code nice and decoupled. Based on where we are we use the different implementations of the interface.

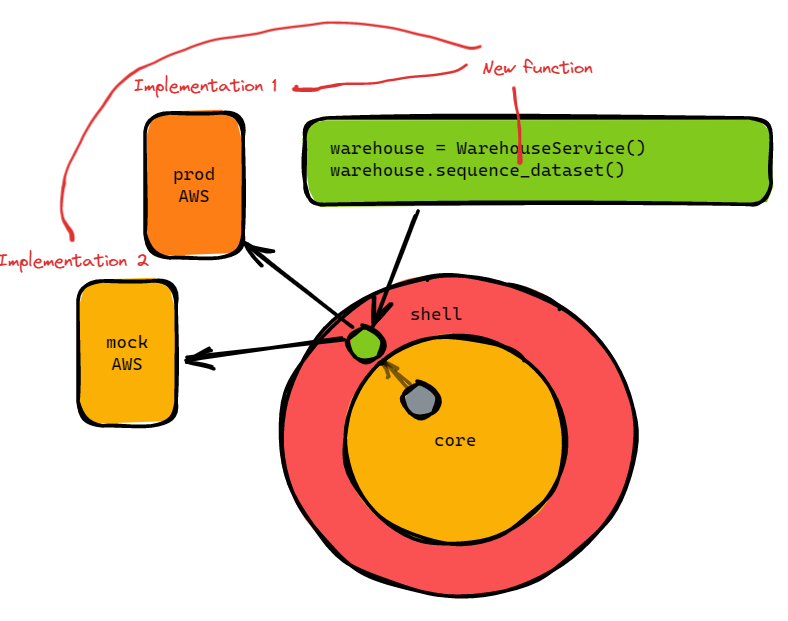

So far we have made the integration test, the entrypoint, and a call to the warehouse, but the call to the warehouse doesn’t exist yet in the interface! We need to change the interface and more importantly implement it for every implementation we have (2 in this case).

Let’s go to the interface and define the sequencing method:

class WarehouseServiceInterface(ABC):

"""Abstraction over talking to Athena."""

...

@abstractmethod

def sequence_dataset(

self,

s3_data_location: S3Path,

sequence_length: int,

output_s3_location: S3Path,

subset_name: str,

) -> S3Path:

raise NotImplementedError

We have created a new method for the interface to call, but that means that we must make two implementations now as you can see in the picture:

The first implementation is the production implementation that hits the real AWS infra:

class AthenaWarehouseService(WarehouseServiceInterface):

"""This one actually connects and talks with Athena. Mocked version is a fixture."""

...

def sequence_dataset(

self,

s3_data_location: S3Path,

sequence_length: int,

output_s3_location: S3Path,

subset_name,

) -> S3Path:

try:

... # do real aws stuff here

logger.info(f"Successfully created sequenced dataset at {output_s3_location}")

except Exception as e:

logger.info(f"Failed creating sequenced dataset: {e}")

raise e

The second implementation is the mocked AWS infrastructure. For us that just means we have some pytest fixtures and upload the data to our mocked s3 server that we run locally through docker.

@pytest.fixture

def mocked_df():

data = {

"is_pad_sequence": [0,1,1,1,1],

"correct_sequence": [1,0,0,0,0],

...

"pupilid_sequence": [1,-1,-1,-1,-1],

}

yield pd.DataFrame(data=data)

Which we then upload during the setup of our fixtures and warehouse

@pytest.fixture

def mock_warehouse_service_setup(

mocked_df,

):

key = s3_key(dataset_name, "train_sequenced_5")

key_with_filename = os.path.join(key, "df.parquet")

upload_df_to_s3_in_parquet(

df=mocked_df, bucket=bucket, key=key_with_filename,

)

but wait, there’s more

As I was typing this up I realized that there is a lot more that needed to be done, such as the CICD pipelines and the other end-to-end tests that need to run. But hey, this is a great start!

Conclusion

This post makes a lot of sense when you read it top to bottom. But remember Steve Job’s words that the dots can only be connected looking backwards. In reality the ticket was a lot harder and took a lot more thinking than what I let on here.

What I really think we have done a great job on is working with interfaces in this repository. When you change somewhere in some routine you immediately are slapped in the face with all the interfaces that you need to change.

This sucks, of course, but at least it is explicit. Is there a worse thing than changing some code somewhere and not being sure if it breaks other code? After starting to heavily rely on interfaces I’ve never felt this pain anymore because the interface will tell me when it will break.

Interfaces are a lot more explicit and honest about the work that needs to be done. If you change an interface you need to change all the implementations, but then you are also done, which is nice. You know that everything is done and everything works.

The tests are also lightning fast because we made the decision to mock our AWS infra locally and have all the data locally. This avoids pulling data back and forth and lightning fast tests are great.

Anyway, the biggest productivity driver on this little piece of work was my time spent investigating. I took some hours to sit down, think the ticket through, and get feedback on my initial design. This got everyone on board with the final design and also uncovered some issues that I forgot initially!

💡 Remember: Spend some time upfront asking validating questions and getting feedback on your design to save significant time down the line.

Comments